The North Sea is a shared body of water between the United Kingdom (UK), Norway, Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, France, and Germany. It’s also home to 184 offshore oil rigs, making it one of the largest offshore drilling areas in the world.

Since the late 1960s, the North Sea region witnessed an oil boom following the Netherlands’ and the United Kingdom’s discovery of oil on their coastlines and out at sea. This oil boom peaked in 1999 at 2.9 million barrels per day in the UK Continental Shelf and in Norway in 2001 at 3.4 million barrels per day.

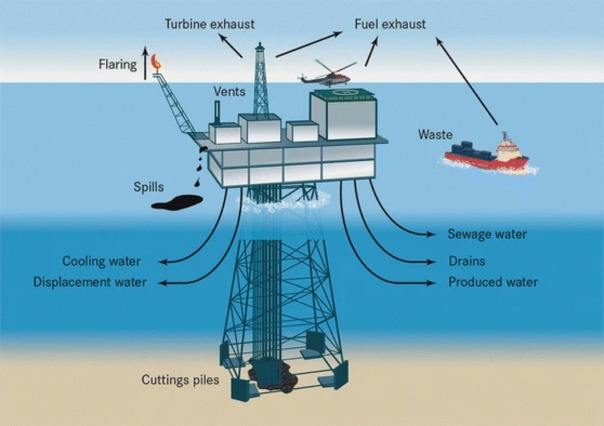

Although these offshore drilling rigs, otherwise known as the upstream sector of oil and gas, cost more to construct and maintain than land drilling, they produce much more oil per day. These rigs also come at an environmental and economic cost. Offshore drilling not only pollutes the oceans and harms the marine ecosystem, but it also pollutes the air, intensifying the effects on climate change. There is a high risk of both accidental spills as well as the release of oil, chemicals and radioactive materials to the sea through the “routine operation of production platforms” according to the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR).

- Figure 1 Source: OSPAR

Between 2000-2011, 4,123 separate spills were recorded in the North Sea, for which only seven oil companies were fined, according to an investigation carried out by The Guardian. Total fines resulted in £74,000 and not a single company paid more than £20,000. By 2014, oil and gas spills were increasing, with the United Kingdom alone reporting a total of 601 spills. A 14.5% increase from 2013.

In 2011, the North Sea saw one of its largest oil spills by Shell due to a leak in a flow line leading to its Gannet Alpha oil platform off of the coast of Scotland. An estimated 200 tons or 1,300 barrels spilled into the surrounding water.

Another spill occurred during 2016 in what BP called a “technical issue,” admitting to a regulatory failure that that led to the discharge of 95 tons of oil within the North Sea. This oil was left in the water to disperse naturally. According to BP, no clean-up of the spill was ever enacted. BP was charged only £7000 in fines.

North Sea Drilling Threatens the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement brought together all nations and was signed in 2016 in response to the global threat of climate change. This agreement created the goal of keeping global temperatures from rising and remaining well below 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, with a target of 1.5°C.

Fossil fuel companies have also pledged to reduce the pollution driving climate change and align themselves with the Paris Agreement, but does this mean that a meaningful transition to a carbon-constrained future is truly underway inside the industry?

In a report released by UK based non-profit Carbon Tracker in 2019, the organization warns investors that before companies can claim to be aligned with the Paris Agreement, they must meet the minimum climate limits. This means major oil companies must reduce their average emissions by 40% by 2040 compared to 2019 levels. It also means that there is very little room for new offshore oil rig projects.

In 2019, the United Kingdom had the highest emissions from oil and gas in the North Sea compared to other producers in the region, reaching 13.1 million tons of CO2, according to data collected by Rystad Energy. In comparison, Norway’s total emission reached 10.4 million tons of CO2 in the North Sea, and Denmark reached 1.4 million tons in the same year. At its current trajectory, the United Kingdom and other European countries will be unable to follow through on a 2050 promise to cut their emissions to virtually zero, according to Carbon Tracker.

Further, the allowance of the development of new offshore drilling rigs is worrisome for these commitments. Norwegian oil and gas giant Equinor, along with its partners Vår Energi, ConocoPhillips, and Petoro announced in September that it would develop and operate drilling rigs in the Breidablikk field – one of the largest undeveloped oil discoveries on the Norwegian continental shelf. In the Dutch North Sea, offshore drilling contractor Maersk Drilling has secured a contract to drill two development wells as part of Project Unity. The first gas from this field is expected in 2021.

Companies that continue to sanction these new projects risk creating stranded assets or assets that are no longer able to earn an economic return. This could destroy significant shareholder value. Additionally, the current emissions goals and targets that major oil companies aim to achieve appear misleading. Many companies’ carbon reduction commitments focus on “Scope 1 and 2” emissions (those resulting from oil and gas operations) rather than “Scope 3” emissions, those generated at the point of oil and gas consumption, where over 90 percent of greenhouse gas pollution from oil and gas happens.

In July 2020, the National Whistleblower Center published a report,“Exposing a Ticking Time Bomb: How Fossil Fuel Industry Fraud is Setting Us Up for a Financial Implosion – and What Whistleblowers Can Do About It.” The report describes why deception about companies’ preparedness for climate change represents a ticking time bomb that, if not addressed, could contribute to worldwide economic devastation. There are two types of fraud that will need to be guarded against as oil and gas companies grapple with solutions to this challenge: exaggerated commitments of future carbon reductions and fraudulent financial statements.

Whistleblowers will be invaluable in exposing actions being undertaken within oil and gas companies that contradict public pronouncements about action on climate change.

The Importance of Enacting Whistleblower Laws

The very first offshore oil rig commissioned in the North Sea was the Sea Gem, a giant barge converted into an oil rig which capsized at sea in December of 1965, killing thirteen people.

Since then, the European Union has created stronger laws to ensure the safety of workers at sea and the clean-up of ocean pollution by enacting OSPAR, the Bonn Agreement, and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). More recently, following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the European Union passed the Directive on Safety of Offshore Oil and Gas Operations to establish comprehensive safety measures and ensure a clean-up response.

However, there are multiple weaknesses in the current legal regime. According to a report by the European Commission in 2018, should an accident such as Deepwater Horizon take place in the North Sea, there is currently:

- No liability in many Target States for most third-party claims for compensation for traditional damage caused by the accident;

- No regime in the vast majority of Target States to handle compensation payments; and

- No assurance in many Target States that operators, or other liable persons, would have adequate financial assets to meet such claims.

Target states include Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, United Kingdom, Iceland, and Norway. Only Norway has legislation that specifically compensates fisheries affected by offshore oil and gas operations and pollution.

Additionally, none of the current laws or EU regulations aimed at this type of oil pollution include whistleblower provisions. Currently, the United States is the number one enforcer of MARPOL in the world because of the whistleblower provision in the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS). APPS was enacted to implement the provisions of MARPOL and permits federal courts to grant rewards of up to 50% of the total fines to whistleblowers whose disclosures regarding pollution on the high seas result in a successful prosecution. Whistleblowers do not need to be U.S. citizens to receive a reward.

The largest reward ever paid for an individual whistleblower was USD 2,100,000 (USA v. Omi Corporation), while USD 5,250,000 is the largest amount ever paid to a group of APPS whistleblowers from the Philippines (USA v. Overseas Shipping). In an analysis of 100 recent APPS prosecutions available on Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER), court records reveal that whistleblowers were responsible for 76% of all successful cases from 1993 – 2017.

Given the fossil fuel industry’s enormous pressure to minimize costs and the fact that much of the work is beyond the scrutiny of casual observers, there is a high risk that environmental and worker safety violation will be concealed. Whistleblowers can play a key role in bringing wrongdoing to light.

In 2021, all 27 EU Member countries will be putting new whistleblower laws into effect following a landmark Whistleblowing Directive passed by the European Parliament in April 2019. Now is the time for European law makers to enact whistleblower laws that will protect and reward those at sea who witness and report fossil fuel companies committing fraud and polluting surrounding waters. To learn more about this new Directive, click here.

To learn more about how international whistleblowers can use U.S. laws, read The New Whistleblower’s Handbook, the first-ever guide to whistleblowing. The Handbook, authored by the nation’s leading whistleblower attorney, is a step-by-step guide to the essential tools for successfully blowing the whistle, qualifying for financial rewards, and protecting yourself.