Assessing Whistleblower Reward Incentives and Caps: What the Data Demonstrates

Evaluating the impact of whistleblower reward caps on incentives for whistleblowers to voluntarily step forward with high-quality information.

Published December 2018

Executive Summary

- Reward laws with caps have universally failed. This is demonstrated by an in-depth analysis of the FIRREA and False Claims Act whistleblower provisions, and the efficacy of those laws over three decades.

- In fact, government agencies which administer the whistleblower reward programs recognize the essential contribution of whistleblowers and oppose reward caps as ineffective. See Sec.

- The SEC rejected the cap proposal in 2011 and no commissioner dissented from that rejection.

- Indeed, no publicly-traded company, bank, or financial institution has supported the 2018 SEC rule change proposal.

- The proposed cap fails the front-pay test for executive compensation.

- The overwhelming weight of authority in the materials provided to the SEC by those who filed comments on this proposal demonstrates that the cap would significantly undermine Congressional intent as well as the overall efficacy of the program.

The National Whistleblower Center strongly urges the SEC to reject the whistleblower reward cap proposal.

The law provides for whistleblower rewards under certain circumstances and caps the highest rewards.

Whistleblower Reward Provision. 12 U.S.C. §§ 4201(d)(1)(A)

The language of the law reads: (i) The declarant shall be entitled to 20 percent to 30 percent of any recovery in the first $1,000,000 recovered, 10 percent to 20 percent of the next $4,000,000 recovered, and 5 percent to 10 percent of the next $5,000,000 recovered. (ii) In calculating an award under clause (i), the Attorney General may consider the size of the overall recovery and the usefulness of the information provided by the declarant.

This means that the most that a whistleblower can receive is $1.6 million, provided that the whistleblower’s information results in at least $10 million recovered, and the whistleblower is awarded the maximum allowed in all segments of that award. This is a 16% reward, within the range of the FCA (the percentage gets higher as the total fine is reduced).

However, additional restrictions apply:

The language of the law reads: “As a general proposition, the maximum fine is set at $1.1 million per violation. 12 U.S.C. § 1833a(b)(1) (1966). See 28 C.F.R. § 85.3(a) (6). For continuing violations, the penalty may not exceed the lesser of $1.1 million each day or $5.5 million in total. 12 U.S.C. § 1833a(b) (2) (1966), as adjusted, per 28 C.F.R. § 85.3(a) (7).” Source.

This means that a $1.1 million fine per violation could result in a maximum $320,000 reward, which is nearly 30% of the total fine, and a $5.5 million fine for continuing violations could result in a maximum of a $1,150,000 reward, which is approximately 20% of the total fine. Note that this is within the range of FCA; in fact, it’s on the high end of it.

A tale of two results: FIRREA

B. The effect of FIRREA on halting and holding accountable financial fraud has been muted.

The effect of FIRREA on halting and holding accountable financial fraud has been muted. Originally passed in the wake of the Savings and Loan Crisis, FIRREA has been derided as a “little-used statute” that has resulted in a “dearth of cases” during its nearly 30 year history.“ Although FIRREA was enacted in 1989, scholars and policymakers have said it was virtually ignored as a vehicle to address financial fraud until the global financial crisis.

Then, for a few years, blockbuster FIRREA prosecutions targeted banks’ behavior precipitating the global financial crisis, including $1.38B from S&P, $5B from Bank of America, $4B from Citigroup, and $2B from JP Morgan Chase & Co. Yet, nearly a decade later, when noteworthy FIRREA prosecutions are compiled by notable experts in the field, they can still be counted on one hand.

Even successful FIERRA prosecutions are attributable to the incentive of un-capped whistleblower reward provisions.

Whistleblower Edward O’Donnell, a former Countrywide Vice President, voluntarily provided original information about widespread fraud by Countrywide Bank under qui tam provisions of the False Claims Act. While the FCA charges were later removed, the government proceeded on FIRREA charges and the parties reached a $1.27 billion dollar settlement, with $57 million set aside for the whistleblower reward.

The qui tam provisions of the FCA triggered the disclosure, even though the case was decided under FIRREA. This is evidence that whistleblower rewards are key to the detection of large-scale financial fraud.

At the same time that FIRREA has foundered, whistleblower cases under the False Claims Act have increased dramatically.

False Claims Act (“FCA”)

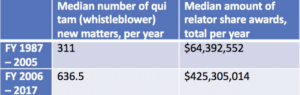

In the 30 years since the passage of the False Claims Act, the DOJ has seen a substantial upward trend in such cases, known as new matters. The DOJ reported that there have been 5,066 new matters over the 19 years between FY 1987 and FY 2005, and 6,914 new matters in just the 12 years between FY 2006 and FY 2017.

These instances are not just submitted tips, but cases in which the government has intervened – and, having determined the validity of these tips, is moving forward.

This trend also suggests that whistleblowers provide better information for law enforcement agents as compared to other ways of investigating or discovering information on criminal activity.

In January 2006, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (“GAO”) reported that the median whistleblower award under the False Claims Act was $123,000. Similarly, according to data released in 2017 by the Department of Justice (“DOJ”), Civil Division, which has prosecutorial jurisdiction over the False Claims Act:

Note that we estimate the average whistleblower reward is $447,830 (this is a very rough average, because of data limitations).

The Story of the Oct. 2018 Mega Millions Lottery

» Worth = $1,600,000,000

» How many bought a $2 ticket?

» Odds of winning = 1 in 302.5 million

» Chance of being struck by lightning: 1 in 700,000

» Chance of becoming a saint: 1 in 20 million

» In just one year, the lottery raised $16 billion for education, $2.5 billion for state general funds, and $1.7 billion for social programs.

Everyone knows it’s true: the widespread publicity of the enormous sum results in a rush to buy tickets.

Dept. of Justice Advocates Against Caps

In 2014, Attorney General Eric Holder, on behalf of the Dept. of Justice, called for the reform of FIRREA’s whistleblower reward provision. He asked Congress to increase the percentage of the reward to 30% of the sanctions imposed – equal to the False Claims Act – in order “to increase its incentives for individual cooperation.”

He pointed out that lifting the caps on FIRREA “could significantly improve the Justice Department’s ability to gather evidence of wrongdoing while complex financial crimes are still in progress – making it easier to complete investigations and to stop misconduct before it becomes so widespread that it foments the next crisis.”

The Dept. of Justice’s concerns about the FIRREA reward cap is equally applicable to the impact on whistleblower perceptions, and in doing so the incentive for whistleblowers to step forward, caused by any reward caps, including the current misguided SEC proposal to implement a cap.

An arbitrary limit disconnected from the reality on-the-ground.

“Like the False Claims Act, FIRREA includes a whistleblower provision. But unlike the FCA, the amount an individual can receive in exchange for coming forward is capped at just $1.6 million – a paltry sum in an industry in which, last year, the collective bonus pool rose above $26 billion, and median executive pay was $15 million and rising”

“In this unique environment, what would – by any normal standard – be considered a windfall of $1.6 million is unlikely to induce an employee to risk his or her lucrative career in the financial sector. That’s why we should think about modifying the FIRREA whistleblower provision – perhaps to False Claims Act levels – to increase its incentives for individual cooperation.”– Dept. of Justice Attorney General Eric Holder, 2014

As A.G. Holder, on behalf of the Dept. of Justice, noted, the median executive pay in 2014 was $15 million – and rising. An individual in this position, who has high-quality information about criminal actions, would not be incentivized to disclose that information using appropriate law enforcement avenues, for such a (relatively) small sum.

In fact, for those with the experience of litigating whistleblower cases, this number highlights why a rewards cap is such a mismatch for the industry. When a court is determining damages, front pay (or future lost earnings) is often used as an alternative to reinstatement, to ensure that a whistleblower who was retaliated against is made whole. McNight v. General Motors, 908 F.2d 104 (7th Cir. 1990); U.S. v. Burke, 504 U.S. 229, footnote 9 (1992). With a cap on whistleblower rewards at $1.6 million in even the best of circumstances, it’s no wonder that whistleblowers are not inclined to utilize FIRREA in the way that the FCA has been utilized over the past decades. As a result, this cap proposal fails the front-pay test for executive compensation.

The SEC Should, Again, Reject a Reward Cap Proposal

FIRREA is an apt comparison for the FCA. The median reward for FCA was $123,000 when the program was audited by the GAO in 2006, and the average awards today are similarly significant. This is less than the maximum reward amount in the FIRREA. Moreover, the reward percentages under FIRREA are within the same ranges as permitted by the FCA. Finally, the FCA and FIRREA have been law for roughly the same number of years, as FIRREA was passed only two years after the FCA.

So, why are the results so drastically different?

» We know that there is in fact fraud at financial institutions, as demonstrated by successful prosecutions under FIRREA on the heels of the global financial crisis. Congress agreed when it passed the law.

» Perhaps Congress intended FIRREA to be much narrower than the FCA. But, it’s highly unlikely that Congress would intend for a law to be widely derided as “little used” and in need of substantial reform, including by the head of the Department of Justice. And, narrow should not mean inefficient.

The FIRREA structure implements the logic of the Chamber of Commerce in advocating for a SEC whistleblower reward cap. It reduces the total reward, using the percentage metric, for whistleblowers who tip the government to fraud that results in certain awards.

This was in fact proposed when the SEC reformed its whistleblower program in 2011 by the Chamber of Commerce and their big business allies, and it was soundly rejected.

“Although we have considered the views of commenters who recommended that the presence or absence of certain criteria should have a distinct and consistent impact on our award determinations, the final rule does not establish such a methodology that would permit a mathematical calculation of the appropriate award percentage…. Accordingly, no attempt has been made to list the factors in order of importance, weigh the relative importance of each factor, or suggest how much any factor should increase or decrease the award percentage. Depending upon the facts and circumstances of each case, some factors may not be applicable or may deserve greater weight than others…. In the end, we anticipate that the determination of the appropriate percentage of a whistleblower award will involve a highly individualized review of the facts and circumstances surrounding each award using the analytical framework set forth in the final rule.”

Whistleblower rewards are a crucial component of an effective program.

Whistleblower advocates who work directly on these laws, as well as the government agency officials in charge of the implementation of these laws, agree with what the data shows: whistleblower reward caps do not incentivize those with information to come forward using the appropriate legal avenues and help the government catch fraud and corruption. It would be highly destructive to the SEC’s law enforcement capacity for the agency to implement any sort of cap in its whistleblower reward programs.

Moreover, the proposed SEC whistleblower cap was been largely opposed by the public; in fact, more than 99% of the comments posted on the SEC’s public comment page spoke out against the limit. The groups that put forth over 3,500 comments in opposition to the proposed changes included whistleblowers, whistleblower attorneys, corporate law firms, as well as Senator Charles Grassley’s office. Much of the criticism focused around the impact the proposed changes would have on the incentive for whistleblowers of large frauds to come forward.

The SEC “whistleblower program . . . has rapidly become a tremendously effective force-multiplier, generating high quality tips, and in some cases virtual blueprints laying out an entire enterprise, directing us to the heart of the alleged fraud.”— Chairman Mary Jo White, Securities and Exchange Commission, Remarks at the Securities Enforcement Forum, Washington DC (October 2013)