The global agricultural industry and commodities trade play a major role in deforestation. More than two-thirds of tropical deforestation around the world is driven by commercial agriculture, and almost half of this deforestation is enabled by illegally converting forests to commercial agricultural land. These figures are expected to increase as demand and production of commodities like palm oil and soy rises.

Commodity-driven deforestation undermines global governance and environmental efforts around the world. Climate Advisers has estimated that illegal deforestation for industrial agriculture is estimated to cost USD 17 billion each year. Indonesia alone has lost an average of USD 4.9 billion per year lost due to conflict, lost tax revenue, and ecosystem function. The loss of tropical forests also plays a major role in climate change, accounting for 15% of global GHG emissions, equivalent to the emissions of the entire transportation sector.

As investors become increasingly concerned about deforestation as an environmental and financial risk, there is a risk that companies could issue false or misleading disclosures about deforestation in their supply chains. Companies could also manipulate investors through misleading key performance indicators on sustainability.

In addition to false or misleading disclosures, the failure to address deforestation risks could raise accounting fraud risks. A report from Planet Tracker warns that natural capital risks, including forest loss, impact financial accounting and financial analysis. Companies that hide deforestation or use unrealistic assumptions about sustainability could overstate the profitability and value of their biological assets.

If companies attempt to deal with deforestation risks through fraudulent schemes, whistleblower-assisted prosecutions could play a pivotal role in curbing complex financial schemes that enable deforestation.

If you need help or want to contact an attorney, please fill out a confidential intake form. To learn more about how NWC assists whistleblowers, please visit our Find an Attorney page.

Material Risks from Deforestation Are Growing

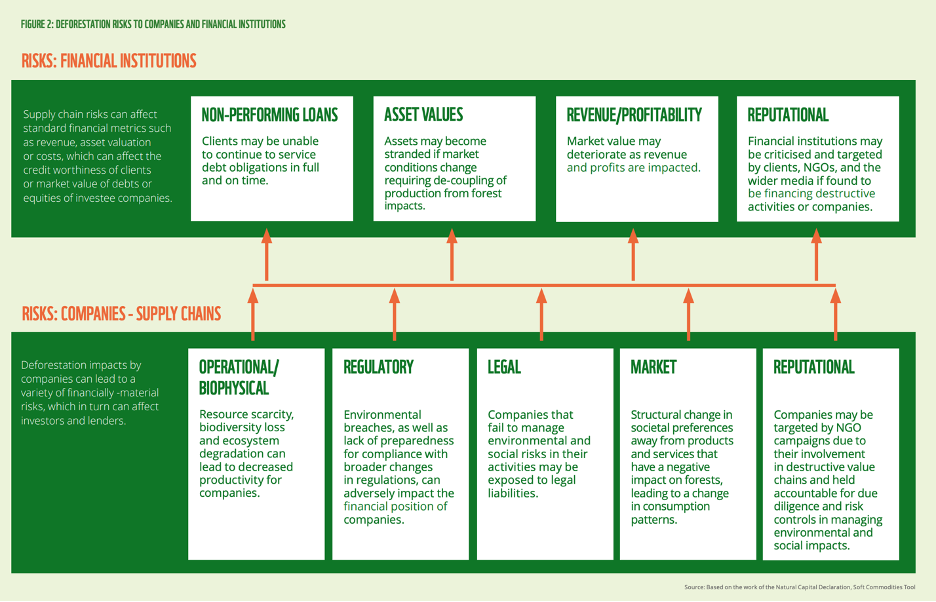

According to Forest Trends, the principal non-timber forest-risk commodities are palm oil, soy, cattle, and pulp. For companies in these high-risk industries, deforestation has increasingly become a critical business issue. Companies are facing growing financial, regulatory, operational, and reputation risks from deforestation.

According to Ceres’s Investor Guide to Deforestation and Climate Change, companies will increasingly face market risks, including the possibility of losing contracts or receiving lower credit ratings if they fail to adjust to new expectations or climate risks, as well as higher production costs due if companies fail to account for physical risks. For example, when the IOI Group, a major palm oil player, lost its Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil certification in 2015, major companies cut the group’s suppliers, and the IOI Group’s share price dropped 7%. When the Environmental Investigation Agency revealed that United Cacao was responsible for mass deforestation in Peru, the company was suspended from the London Stock Exchange.

With investors and consumers increasingly concerned with deforestation, companies, particularly consumer-facing companies and retailers, will also face greater reputation risks associated with deforestation. Stronger regulations on deforestation, the illegal timber trade, and carbon emissions could create new regulatory risks, and both transition-related and physical climate risks will also affect key assets; these impacts could lead to shifting production zones or even stranded assets. The crackdown on the development of peatlands through the “no-deforestation, peat or exploitation” (NDPE), has meant that 30% of palm oil concessions in Indonesia can no longer be developed. As a key driver of climate change, deforestation also exacerbates broader climate risks that will affect many other industries.

- World Wildlife Fund, “Banking on the Amazon,” (2016).

Voluntary Commitments Provide Deceptive Reassurances

According to a shareholder advocate with Green Century Capital Management, “if a tree falls in a forest, investors want to hear it.” Investors increasingly want companies to disclose details about how they are handling deforestation in their supply chains. A number of key investor groups have pushed companies to take deforestation risks seriously, including an initiative by Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), a global investment standards group on sustainable palm oil and an initiative by PRI and Ceres on sustainable forests.

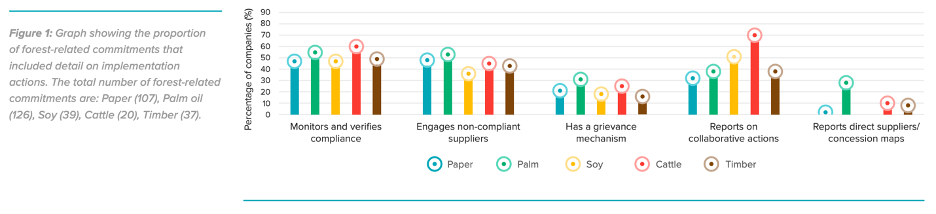

As a result, the last decade has seen a major proliferation in voluntary company pledges to tackle deforestation, with hundreds of companies committing to eliminate deforestation from their supply chains. Some companies have made “deforestation free” commitments. Others have made “net zero deforestation commitments,” pledges to plant an equivalent amount of trees elsewhere, although “equivalent” is difficult to define. In 2010, four hundred companies in the Consumer Goods Forum, including big names like Nestle, Mondelez, and Unilever, promised to end deforestation by 2020, and the biggest palm oil producers and traders promised a zero-net deforestation by 2020.

A decade later, however, companies have not made much progress on these promises and the level of ambition expressed in corporate statements does not appear to correlate with actual commitment. In 2019, a report by Global Canopy examined the 500 most influential companies in forest-risk commodity supply chain, finding that not a single company was on track to meet their deforestation pledge. The report also found that 40% of these companies were not doing anything to tackle deforestation in their supply chains.

While many companies are eager to sign vague commitments, they have been reluctant to provide details. When the corporate sustainability group CDP asked 1,500 companies to disclose information on deforestation in their supply chain, 70% of the companies declined. Of the 306 companies who did report information, a quarter were taking little or no action.

- Global Canopy, “Annual Report 2018: The Countdown to 2020,” (March 31, 2019).

Commodity-driven Deforestation Scandals

Companies use a variety of deceptive methods to hide deforestation from regulators, investors, and consumers. JBS, the world’s largest meat producer, successfully projected a global image of itself as a sustainable supplier, as the founder of the Global Roundtable on Sustainable Beef, before Greenpeace alleged in 2012 that the company had been purchasing beef from illegally deforested ranches. These allegations were confirmed in 2017 when the Brazilian government raided JBS facilities, finding almost 60,000 cattle from illegally deforested land.

A subsequent investigation revealed a web of corrupt practices that enabled the company to hide its links to deforestation, including fraudulent financial transactions and USD 185 million spent on bribing 1,900 politicians. Ultimately, JBS was forced to pay the Brazilian government USD3.2billion. Combined with the broader reputational damage, the scandal cost the company USD 2.3 billion in market value. The scandal also ensnared JBS’s parent company, which ultimately pleaded guilty in the U.S. to violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and was forced to pay USD 128 million.

Another recent report highlights how companies could hide deforestation, despite no-deforestation pledges. In October 2020, a coalition of environmental investigative groups accused APRIL, one of the world’s largest pulp and paper producers, of violating its own deforestation policy by sourcing wood from a company clearing rainforest in Indonesia. Based on satellite imagery, their report documents extensive deforestation, including the clearance of forests on peatlands in the concession area of one of APRIL’s top wood suppliers.

The investigation suggested that companies could be using opaque beneficial ownership structures to hide their ownership or control over suppliers engaged in deforestation. Using documents exposed in the International Consortium of Investigative Journalism’s Offshore Leaks Database, the report identified a complex link between the two companies, contradicting APRIL’s earlier claim to not having ownership or control over the supplier, as well as holding companies in offshore tax havens and links to tax evasion.

The report also criticizes auditing company KPMG for providing legitimacy to the company’s zero deforestation pledge through “assurance reports” without detecting or reporting this deforestation.

How Whistleblowers Can Reveal Hidden Deforestation

Without enforcement, voluntary corporate commitments are unlikely to halt rising deforestation, and these commitments may mislead investors more than they protect forests. With a range of ways companies could hide deforestation risks, whistleblowers will be crucial in revealing hidden deforestation risks, as well as corruption that enables them.

While individuals with knowledge of fraud or corruption often face significant obstacles to reporting locally, whistleblowers around the world can use powerful U.S. whistleblowers laws to confidentially report to U.S. law enforcement. The Dodd-Frank Act allows whistleblowers both in the U.S. and abroad to confidentially report companies who violate U.S. federal securities laws. If companies mislead investors about their role in deforestation, whistleblowers could turn to the Dodd-Frank Act.

Whistleblowers can also use the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act to confidentially report bribery that enables companies to hide deforestation. The FCPA is extremely broad in scope and applicable worldwide. It applies to all U.S. or foreign companies required to file periodic reports with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, and it extends to a company’s employees, officers, stockholders, and agents such as third-party actors, distributors, and consultants.

Additionally, violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act are also predicate offenses for money laundering under U.S. law. Whistleblowers around the world can use the IRS whistleblower program to confidentially report companies who bribe foreign officials to obtain land concessions or logging permits and then conduct transactions in the U.S. financial system with the proceeds, along with the third parties who facilitate these transactions.

While corporate deforestation pledges have often gone unchallenged, whistleblowers have the potential to change that by revealing both attempts to mislead investors about deforestation and by revealing the corruption that enables misleading claims. With powerful U.S. whistleblowers laws, whistleblowers have the potential to provide a missing enforcement tool, while protecting their identity and qualifying for a financial reward.

To learn about the Dodd-Frank Act and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in more depth, read The New Whistleblower’s Handbook, the first-ever guide to whistleblowing. The Handbook, authored by the nation’s leading whistleblower attorney, is a step-by-step guide to the essential tools for successfully blowing the whistle, qualifying for financial rewards, and protecting yourself.